[occasionally, if he’s had a particularly successful night of preying on small rodents, contributing writer and local night-owl marrrrrrr swoops down toward the local drive-in to rest his wings while watching an engrossing thriller and pecking at the stale popcorn littering the ground. this is Midnight Movies.]

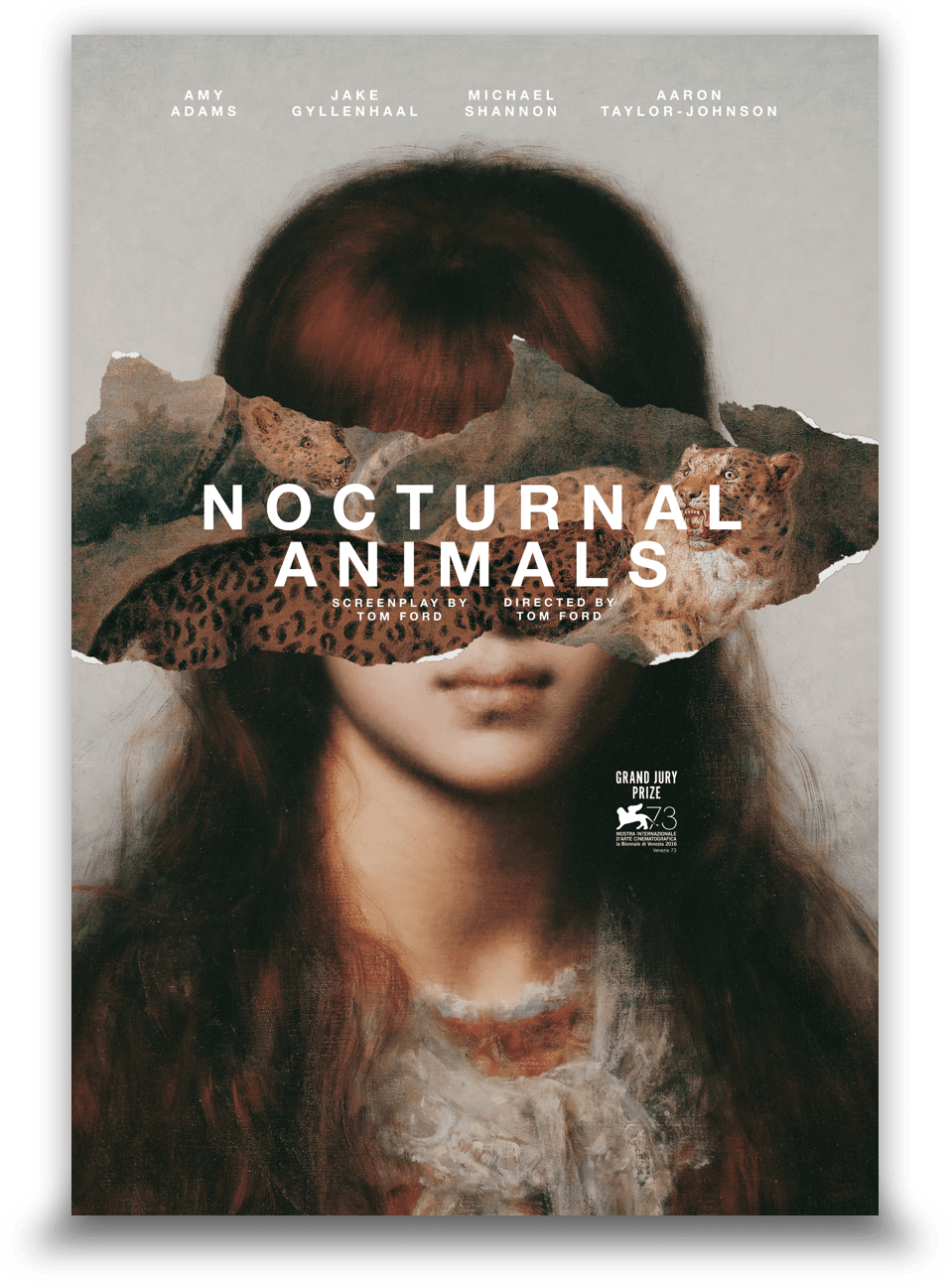

pre-game: tom ford’s follow up to A Single Man (2009). don’t know much about it other than darker and w/ a stellar cast (amy adams, jake gylennhaal, michael shannon have top billing). his first was surprisingly stylish for a first-time director (altho.. maybe not so much of a surprise considering his main gig is fashion design). post-game to follow

post-game: Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals could be summed up as a study in a series of seeming dichotomies (the beautiful vs. the grotesque, the masculine vs. the feminine, romanticism vs. cynicism, urban vs. rural, fiction vs. reality) tied together by the suggestion that, ultimately, all these dichotomies are false.

the last of these is the most immediate. after tinted and tightly coiled gallery owner susan morrow (Amy Adams, darker here than she’s been since Cruel Intentions 2 (2000)) receives a manuscript of her ex-husband’s soon-to-be-published thriller titled (you guessed it) “Nocturnal Animals,” she tears into it, desperate for something to keep her mind occupied during her well-known bouts of insomnia, thus becoming the framing device for the film’s story-within-the-story: the tense and tragic tale of tony hastings (Jake Gyllenhaal in a dual role).

en route to marfa, texas with wife (Isla Fisher, whose resemblance to Adams is too deliberate to be coincidence) and daughter, the hastings are run off the road by a trio of thugs led by local sociopath ray (Aaron Taylor-Johnson, punching considerably above his weight class at the time). the encounter turns violent, the women are abducted, and tony wakes up alone in the texas desert, still not quite able to process what the hell went wrong.

as susan becomes more engrossed in the novel, she begins to reflect on her life and her choices, specifically the ones she made regarding her ex, edward (Gyllenhaal, notably, again). their story is told in flashback sprinkled throughout, and, as it’s exhumed, it becomes increasingly clear that the novel (dedicated to her and inspired by their marriage as noted in a personal letter that accompanies the manuscript) is maybe-but-not-definitely-but-probably a partial metaphor for their relationship.

from there, the film flips seamlessly and mostly cleverly between the two narratives (cheers: edward bathed in the red glow of tail lights bleeding into tony’s face illuminated by red neon. jeers: transitioning between something violent in the novel to an unexpected noise in susan’s house (a pop of wood in the fireplace, for example) was a well dipped into a few times too often), subsequently collapsing all the dualities mentioned above: is cruelty on a highway under a harsh west texas sun really different from cruelty over a posh dinner table delivered with a smile? is a punch to the face better or worse than a loved one using the coldest possible words to strike at a known insecurity?

regardless the setting, the film is gorgeous throughout. Ford displays the same sense of style he showed in A Single Man (2009): zooming in on the rap of some fingers on a car top to heighten tension or mirroring corpses with naked lovers entwined in similar poses.

the performances, too, are uniformly excellent, which pretty much goes without saying when you can get a heavy hitter like Laura Linney to sit and sip martinis in a big southern wig for five minutes and almost steal the show. Andrea Riseborough (maybe the most undervalued working actress) does just as well with even less screen time: decked in an afro and heaps of turquoise, she sucks in her cheeks, waves flamboyantly, talks about the benefits of her gay husband, recommends a psychopharmacologist, and overall uses a bit role to create a better send-up of Hollywood vapidness than a thousand talk radio rants.

and that’s all before mentioning Michael Shannon as fictional detective bobby andes. although, Shannon’s standard is so high at this point, it would be more noteworthy if he wasn’t best or near-best in show.

where the movies struggles is by falling ill to the same problems that commonly plague frame narratives.

first, mixing the two stories isn’t quite a “toothpaste-and-orange-juice” situation, but both are slightly weakened as a result. the novel’s plot is somewhat excused for having a few underdeveloped character choices and lapsing into melodrama since it’s, potentially, the in-universe creation of a character deliberately being heavy-handed to make a “point.” on the other hand, susan’s story doesn’t have the same kind of built-in justifications.

why is it that susan ultimately left edward? she repeats several times that it’s because she’s “a realist,” but all that seems to mean is that edward’s one-bedroom place in austin is too humble for her. and if material wealth is the issue, as her mother suggests, what of the fact that she seems perfectly capable of making her own money? or is edward right and the real reason is that she’s afraid? and if so, why? and why does she stay in a loveless, faithless marriage for the subsequent 19 years? it’s not that these choices couldn’t be explained, but that the occasional wisps of dialogue purporting to explain them feel obligatorily provided, not to give susan depth, but purely to set up the frame.

secondly, and more noticeably, Nocturnal Animals makes the mistake of making one story imminently more compelling than the other. it’s hard to compare the visceral crime thriller being told in the novel to the mid-life awakening of the depressed multimillionaire reading it. and since the novel is established as fictional in-universe, even the suspense established there is mitigated by the knowledge that the events “don’t matter” for the “real characters.”

it’s to the film’s credit that it remains captivating throughout, even when focusing on what can feel like the “weaker” story, and, once the metaphor of the novel is established, there’s still a certain fascination with puzzling out the symbolism of the book as it relates to the characters in the framing story. Ford’s screenplay practically begs for the audience to bust out their literary degrees and get analyzing who means what and why, all while providing enough thematic cannon fodder for an entire career’s worth of different academic readings.

it’s also worth noting that the film’s final blow, delivered masterfully with a few twitches of Adams’ blue eyes, is just as devastating as anything in either plot.

so which is the reality? did Tom Ford craft a complex puzzle of a film with an uncanny depth designed to implicate a whole range of complications of the contemporary human experience? or is Nocturnal Animals an unnecessarily convoluted mixture of two intriguing stories that would have been better told separately?

the answer, of course, is yes.

rating: