[once every federally-mandated lunch break, contributing writer and part-time corporate drone marrrrrrr punches a time card, grabs a meal out of the fridge, and sits down to enjoy a film: the one brief glimmer of joy necessary to survive in the soul-sucking hellhole of a white collar office space. this is Midnight Movies.]

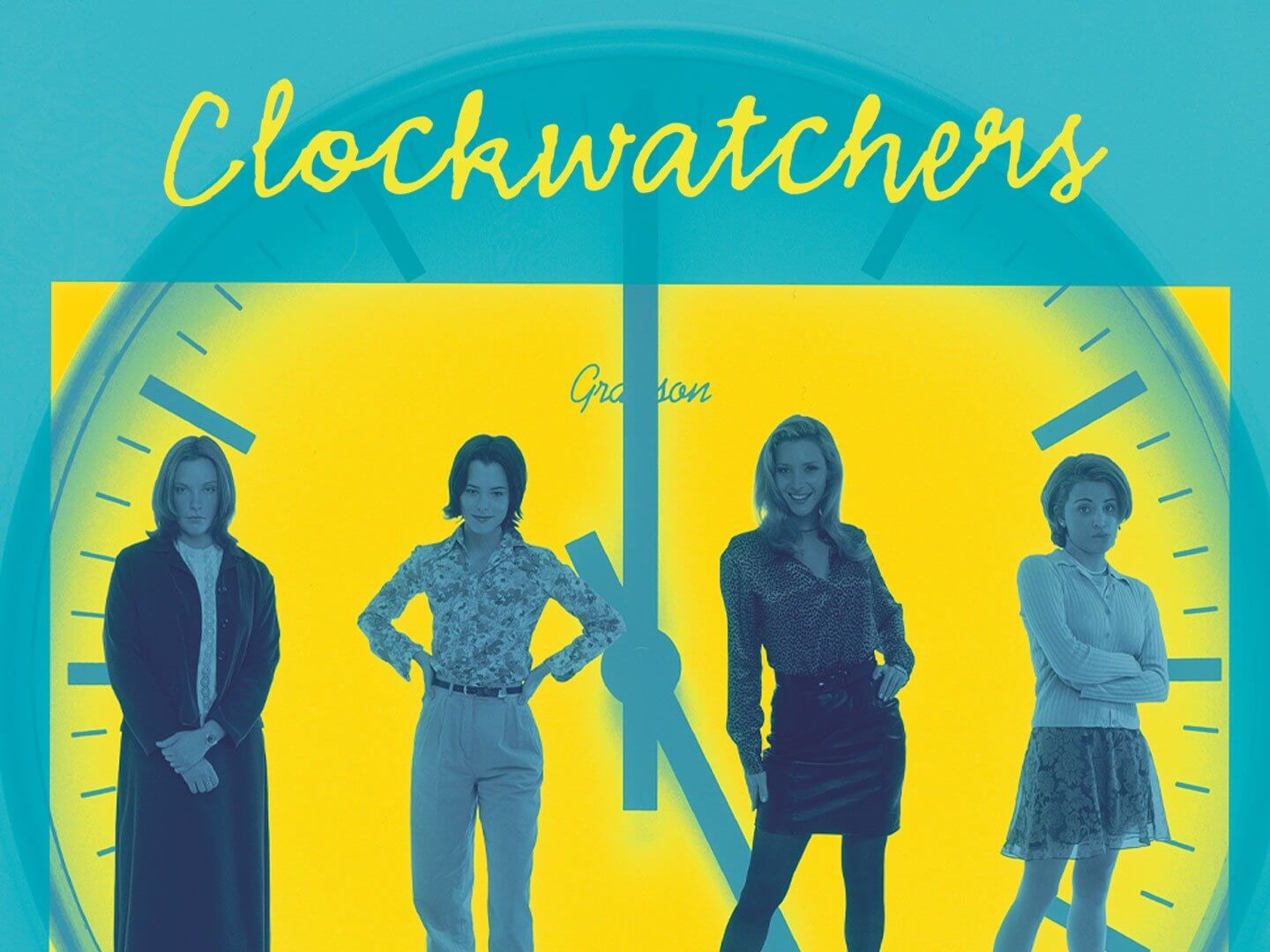

film: Clockwatchers (1997)

food: … probably some popcorn?

pre-game: indie about four female temp workers from jill sprecher (who later directed 13 Conversations About One Thing (2001) which i really like and is highly recommended for anyone into “bittersweet anthology films where not much happens, but you walk away vaguely feeling wiser and somehow both more (general) and less (specific) connected to the rest of humanity”), so i’m looking forward to it. stars parker posey, lisa kudrow and toni collette, so probably well-acted if nothing else.

post-game: now over two decades since its initial release, Jill Sprecher’s Clockwatchers is an especially interesting watch in a world seemingly obsessed with the possibility of automation. as Toni Collette’s iris narrates near the start, “there are two types of time: mechanical and human.” this won’t be the only time the conflict between workers and machines (or the treatment of workers as machines) is highlighted. (for example, when one character’s time card goes missing, another casually breaks open the punch clock to start a new one.)

was Sprecher hinting at an increasingly likely social problem? mass automation of labor, after all, was a slightly less looming, but not entirely foreign, possibility in the late 90’s.

or was she driving at an unspoken reality of the corporate workforce: that the ideal worker, especially at the lowest rung of the “ladder,” lacks any traits of humanity entirely?

iris chapman, taking work as a temp to stave off what feels like her inevitable absorption into the same sales company as her father, winds up filling in at a credit company. on her second day, she meets maragaret, paula and jane (Parker Posey, Lisa Kudrow and Alanna Ubach, respectively), the other temps on her same floor, who clue her in that the “temporary” assignment might be surprisingly long-term. the company, it turns out, hires and keeps on temps to avoid having to pay benefits. anyone who’s worked either gig, an internship or “freelance contracting” will recognize the general ruse.

the four become friends, bonding over their general mistreatment (no-one else on the floor, including their immediate supervisor (Debra Jo Rupp), knows their names) and penchant for small mischief (maragaret takes unauthorized smoke breaks in the bathroom, paula deliberately jams the office copy machine to flirt with the handsome repairman, and jane, the group’s bride-to-be, makes personal calls to plan her wedding).

the friendship grows mostly unabated, until money and items around the office start disappearing: a lewd coffee cup, the break-room donation can, a shoe, some spoons, and a small plastic drink decoration iris saved from her first night out with her friends.

it doesn’t take long for the company to zero in on the four temps as the most likely culprits. the result is a series of daily humiliations: an open desk layout monitored by newly installed cameras, “random” desk searches, hovering supervisors, and interrogations by the police.

the degradation begins to wear at the bond between them and, even though they know this is part of the company’s intent, animosity and suspicion begin to creep in. and all the things that the women use to define themselves outside of the job are revealed as either traps or delusions. jane’s impending wedding is to a boyfriend of dubious faithfulness and quality. paula, a wannabe actress, is potentially fabricating tales of auditions and rehearsals. margaret’s hopes for a better position are dashed when the executive she’s grown closest to suffers a fatal heart attack. (“try getting a recommendation out of a dead guy,” she quips.)

when the thief is finally revealed, the behavior is immediately understood as something similar: a way to insist on one’s own humanity in an environment that would prefer you not to be human at all.

as the title suggests, much is made in Clockwatchers of time. the film opens with the monotonous ticking of a clock. the women are admonished for leaving a few minutes early one day and asked to adjust their time cards as a result (after all, they’re on “company time”). iris notes how everyone in the office seems to just be “killing time,” because, “down time,” of course, is something that should never exist at all. as margaret puts it, “the only real challenge with this job is trying to look busy when there’s nothing to do.”

a machine, with its optimized efficiency, would never have these problems. you could simply switch it off when 5 o’clock rolls around, or power it down whenever it’s not in use. humans, conversely, keep persisting. yet, so often, they are (as iris, glaring up into the camera in the movie’s final shot, vows never to do) “just waiting and waiting and watching the world go by.”

rating: a Massive Attack remix of “9 to 5.”